Monday 26 September 2022

In Conversation with Mandeep Dillon

Mandeep Dillon is one of the artists selected for Orleans House Gallery’s 2022-2023 Emerging Artists Programme. We asked her some questions about her practice and Objects of Disquiet, the site-specific installation she put together for our space, open for visits from 27 August to 9 October 2022. If you would like to speak to her too, come to our event ‘An afternoon with the artist’ on 30 September, from 2-4pm. Find out More

Mandeep, could you say a little bit about yourself and what or who got you into art?

I studied sculpture at the Royal College of Art, graduating in 2019, but it took me a while to get there. I grew up in a working-class household with immigrant parents during the 1970s. We had few material possessions and life was very much about making do with what we had. Looking back, this may have stimulated my desire to make and create. Although my sister and I had few toys, we did have an old suitcase which we turned into a dolls house, building cardboard rooms and furniture cut out of old catalogues. Perhaps this is where I began my collage making and working in three dimensions. I also had a treasured broken clock that I constantly took apart and pieced back together, although I never actually managed to get it to work. I often became absorbed for hours on end making things out of odd bits and pieces and I have been doing this ever since.

Drawing and sculpture were the only subjects that I excelled at in school and in many ways these subjects became my saviour. I recently had some tests which revealed that I am dyspraxic and dyslexic. Back in the 1970s, however, such conditions were poorly understood. Making art wasn’t encouraged at home, but I did have two wonderful art teachers who made all the difference. Although I was always passionate about studying fine art, I decided to complete a degree in interior architecture because I felt I needed to support myself financially.

I eventually became a filmmaker for NGOs and later for mainstream TV because I was interested in social issues and people’s stories. I worked in locations where I witnessed conflicts and extreme environmental events. During this period, I continued to draw and paint as well making short experimental films.

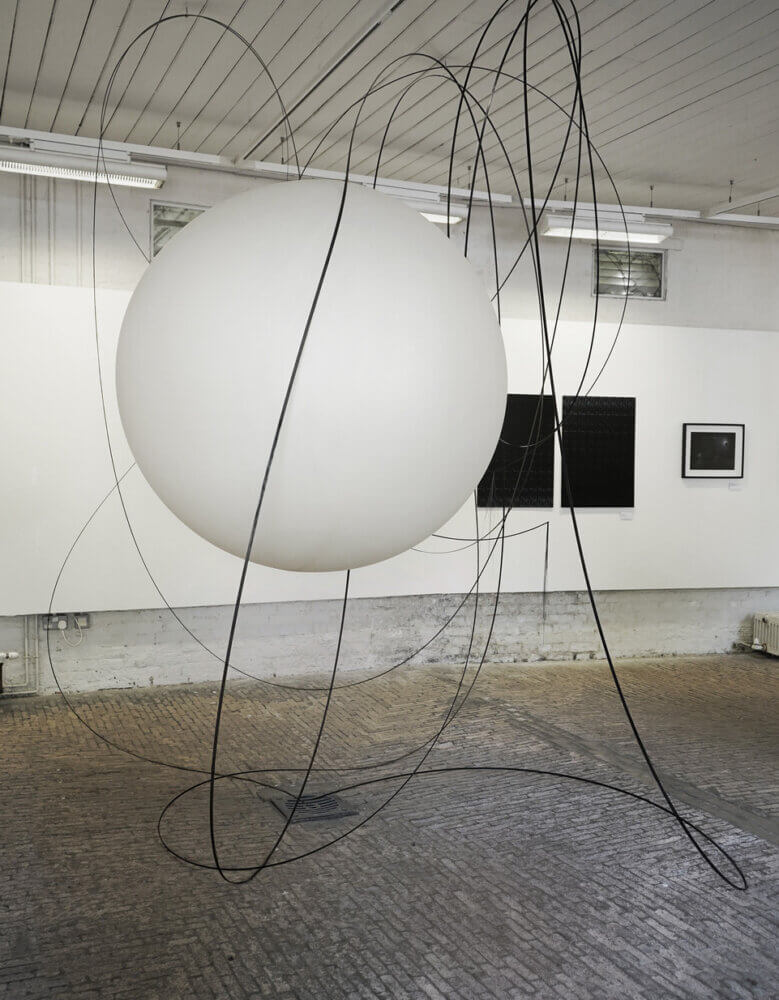

'Fluctuant' sculpture designed by Dillon for Objects of Disquiet exhibition at Orleans House Gallery

Objects of Disquiet, the show that is at our gallery now, is ‘a comment on the ephemeral nature of human and non-human existence’. Could you tell us a bit about this theme and how this is connected to environmental discussions?

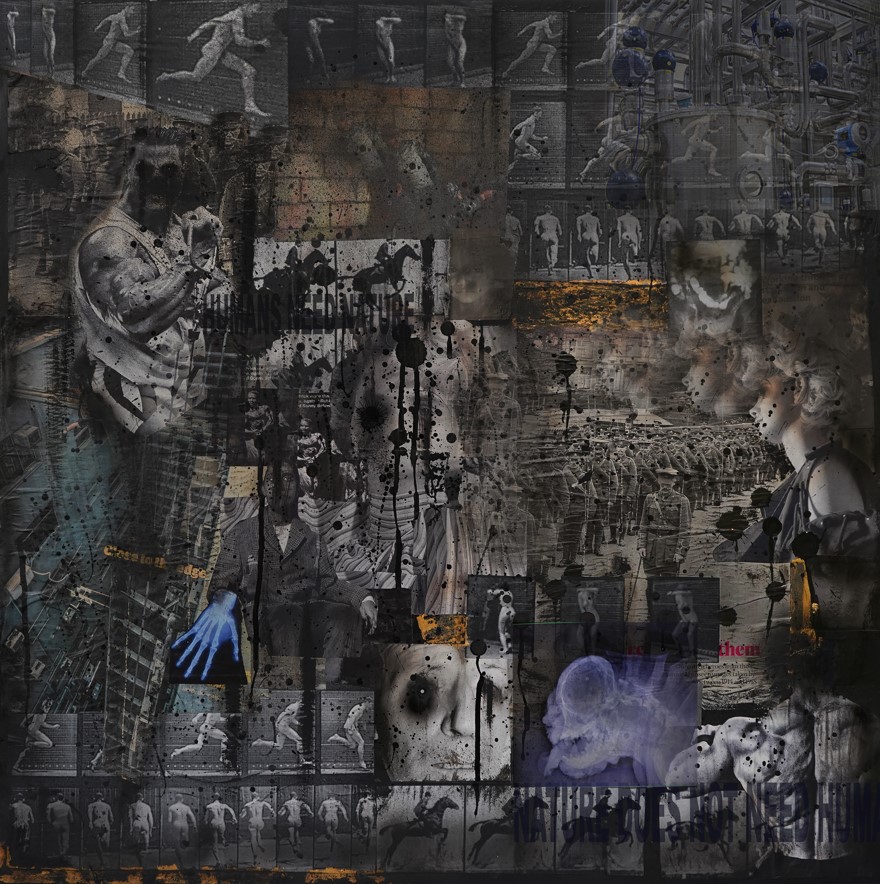

The work on display in the gallery considers the fragility, vulnerably and ultimate mortality of the body. I use the term body in the broadest sense and without making distinctions between human or non-human entities. This is an important aspect of my practice as I think that anthropocentrism, the elevation of the human above other life forms, has sanctioned the use of nature as a free resource without consequence. The chicken is used as a microcosm of these ideas and to explore our relationship with other animals. The farmed chicken is the most common bird species on earth and the most widely consumed food animal on the planet. Caged hens are an extreme manifestation of our fractured relationship with nature. The Swan Lake collage is a digital amalgamation of different images of battery farms. The hens are kept hidden from sight in relative darkness, all facing a central aisle. The space is reminiscent of a theatre or auditorium. The hens appear to be watching a show – the sorrow of Swan Lake. The dying swan, Odette, was an apt addition to the scene: with the pathos of the dancer comes the sublime, emphasising the misery of the conditions in which the hens live.

Similarly, the placing of my daughter’s and her doll’s hair on the chicken in two of my works is an attempt to give agency to a creature that has none and raise questions about our own sense of ourselves as either animals or humans. Has a human element been added to the chicken or has the chicken been added to the human? Theodor Adorno, a leading member of the Frankfurt School’s of critical theory, believed that anthropocentrism came from a fear and shame that we are in fact nothing but animals. Humans feel a revulsion from everything that might remind us of our own innate animality.

I have been involved in environmental issues since I was a teenager and my art practice is an expression of the sense that we have reached or surpassed a tipping point. Some of the works have both synthetic and seemingly biological attributes. Looped steel is falling in cascades, invoking a sense of fragility and instability. The balloons are in a constant state of flux all subtly deflating, while others collapse or implode during the course of the exhibition. The works become interactive in response to approaching viewers, their movement triggering the unstable and more fragile components to bob or sway prompting an awareness of our own embodied relationship to the objects.

The title of the work ‘Gradually, then Suddenly’ is a line from Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises. There’s a passage in which a character named Mike is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he answers. “Gradually, then suddenly.” Ecological breakdown is following a similar trajectory. On a daily basis it is imperceptible. As we continue to grow, consume and pollute, a tipping point may be reached where the Earth is unable to recover, resulting in biodiversity loss and climate change followed by feedback loops and accelerating cascades.

Image of the collage 'Holocene', 2019, currently part of Objects of Disquiet show

In your opinion, what is the role of art in the environmental challenges we are experiencing as a society?

Art plays a powerful role in expressing and communicating the environmental challenges we face in the 21st century. When making art at any level of skill, accomplishment or experience, we can deepen our knowledge through the act of looking, understanding and trying capture what we observe. Art in its various representational forms has always depicted the wonder and beauty of the natural world. But it can also reveal its vulnerability and fragility. Art can show the impact of our actions through images of environmental destruction. It plays a role in environmental activism. For example, the branding of Extinction Rebellion and the imaginative presentation of their political actions is ground-breaking in helping to promote awareness and stimulate dialogue.

I sometimes question the purpose of making art for an audience who in most cases are sympathetic or attuned to the issue of environmental breakdown. In rare moments of optimism, I hope that art can play a far-reaching role as a catalyst for change and stimulus for action in society. But I think more realistically art can at least be compelling and thought provoking. Perhaps that is enough.

Making art political to achieve change is difficult because it can too easily become literal, didactic or sentimental. I constantly question whether my own work falls into these categories. The strongest political or ecological art is subtle, poetic or even humorous. Because making art consumes resources and in most cases creates new objects, I often wonder whether it is ethical to produce more ‘things’ when the world is already full of human-made artefacts. I know many artists who re-configure found objects into sculpture and that’s certainly the more sustainable approach. In my own case some of my work appear quite large but the materials I use either deflate or the metal coils up into small pieces, which I try and use again in different forms.

You talk about your work as an artist being meditative. How does that translate into your practice?

The process of creating art can be rewarding, but it is often painstaking and fraught with challenges. Making installations requires an enormous amount of trial and error, and experimentation with different processes and techniques. I sometimes work with combinations of materials to create a particular effect. However, these objects can be fragile yet need to be able to withstand being in a gallery setting for a long period of time.

I have recently gone through a period of trying to make small fans produce specific flows of air without over-heating, or being too noisy or obtrusive. Needless to say, this is an on-going project and I’m still looking for that ‘Goldilocks’ moment.

People may wonder why artists endure these trials and tribulations. Making art can be a solitary and difficult pursuit. But the upside of all this is the opportunity to immerse oneself in a creative process, being totally absorbed in an activity which becomes an almost mediative act. Psychologists call this being in a state of ‘flow’. It occurs when a person engages in a creative task requiring a high degree of skill and concentration and becomes completely focused, with no space for distraction.

Dillon explores the shapes and forms of red ballons in 'Ripe'

What or who is your inspiration today and how is this changing your style or subject matter?

I have always been interested in philosophy that explores the relationship between humans and nature. I am curious to understand why our sense of ourselves is based on human exceptionalism. Peter Singer’s writings on the rights of animals had a huge influence on me as a teenager and more recently thinkers, such as Rosi Braidotti on Post-Humanism, have informed my art practice.

I am also inspired by lots of incidental things such as the way something moves or sounds. This could be the sight of a plastic bag hanging on a branch of a tree or beetroot cut in half. I take lots of photographs of seemingly random things, which may subconsciously inform my work. Early this year, for example, I noticed that someone had left an artificial Christmas tree in the road. To me, it resembled an old woman resting against a wall. She was there for weeks and I kept expecting her to fall or walk away from the scene. I think this resonated with me, because some of my work appears to be standing precariously or about to fall. This sense of impending collapse is something I keep returning to.

'Leaning Christmas Tree’ by Mandeep Dillon