Friday 5 February 2021

Collection Focus – Hidden History – The Borough’s Domestic Grottos

In the next article in our continuing Collection Focus series, volunteer Ella discovers the rich history of grottos in the borough through a series of Borough Collection artworks.

There is something distinctively intriguing about the idea of a grotto that has sparked human interest throughout past centuries. Inspired by Hellenist traditions, the popularity of artificial grottos as part of garden design soared in the sixteenth century Mediterranean nations. Eventually the feature was employed within several English landscape gardens, including many within Richmond Borough: at Marble Hill, Hampton Court and of course, Alexander Pope’s villa. They stood as concealed jewellery boxes, filled with shells, precious stones, fossils and statues, as they provided a space for the wealthy to retreat for inspiration and indulgence. It is notable that there is a staying power with a grotto, in that they are frequently the remaining fragments of gardens and houses long destroyed. Often constructed to look like nothing more than a humble cave or leafy enclosure, the façades give way to something akin to temples, places where a mermaid or naiad would not seem out of place. Sadly, since the British picturesque movement, the popularity of grottos diminished, and their construction was once again resigned to history.

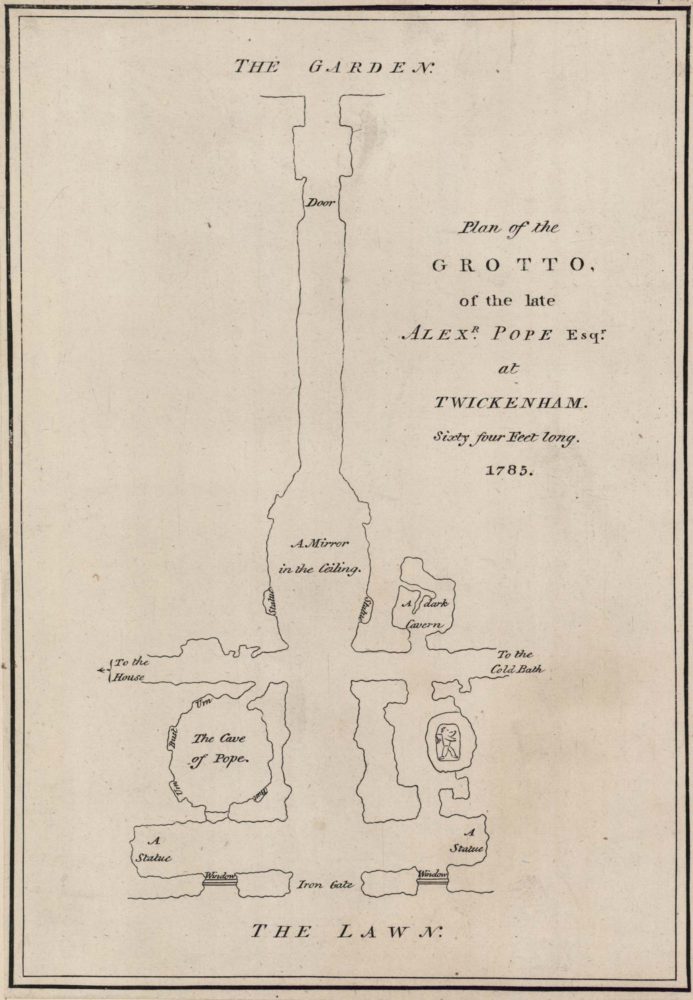

Within Richmond Borough, we are lucky to still have many remaining examples of these caves of curiosities. Residents may be surprised to discover that underneath the tarmac road of Cross Deep, Pope’s own grotto still survives, relatively untouched, just as I was before starting volunteering at Orleans House Gallery in the summer of 2020. Frederick Bracher notes just some of the eclectic pieces that make up this bohemian poet’s Nymphaeum, stating “the walls were finished with crystals, blood-stone, amethyst, and ores. A statue stood at either end, and the porch was finished with curious-coral, petrified moss, a humming-bird’s nest [and] two stones from the Giant’s Causeway”.[1]

This plan of the grotto [above] illustrates to the modern viewer the attempt by Pope to create a space that not only blurred the lines between artificial and natural in the objects within, but also in the layout. He created ‘caves’ and ‘caverns’, small and intimate areas sculpted out of natural rock, and yet they remain intertwined with the lexicon of domestic property. For instance, the plan shows a route ‘To the House’, ‘To the Cold Bath’, it includes a mirror, a ceiling, windows, and a gate, terms of domiciliary.

Whilst I was musing this fact and the curious way that Pope and his gardeners pursued this liminal state, I looked over some of the pieces in Orleans House’s collection. I wanted to see if these themes or indeed grottos themselves appeared in any other local artwork. In doing so, I discovered a motif that was even more intriguing. Heralding mainly from the Ionides Collection, I noticed that in depictions of local property, the buildings had often been framed, or obscured to a point, within an Arcadian pastoral – just as a grotto is disguised.

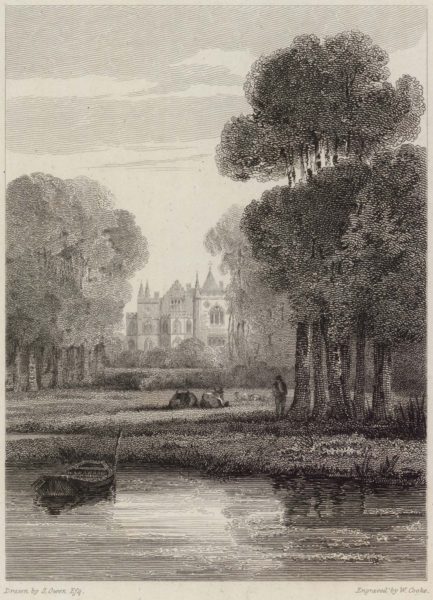

G. Presbury’s print of Pope’s Villa (sadly demolished by the ‘Queen of Goths’, Baroness Howe of Langar, in the early 1800s) places the grand house behind the Thames and trees. The foreground boldly dominates the composition to a point where it may take a while for the viewer to see past the cattle and foliage to the property itself. This type of framing is something that will be evident in the other artworks explored in this article, all standing as clear examples of the ideal classical landscape formula. This technique was most concretely established by French artist Claude Gellée. The trees are almost like the curtains of a theatre, they add depth and draw the eye inwards. We also begin to get the cyclical gaze that mirrors looking into a telescope, an act of attempting to find something, or gain a better view. The house stands as a treasure to be discovered, a man-made structure that mingles with the natural landscape.

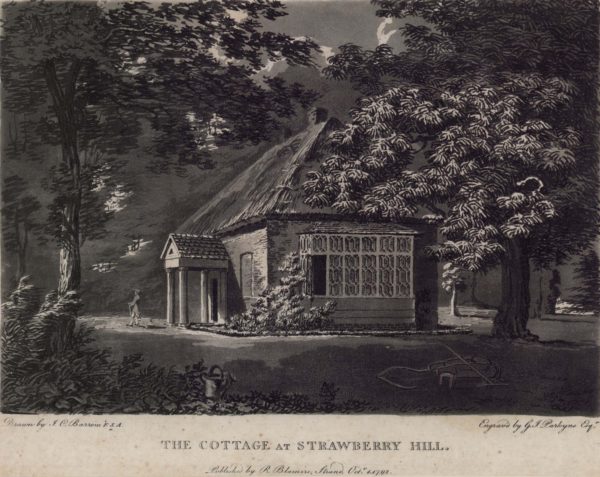

On a much more modest scale, the following print, drawn by J. C. Barrow and engraved by George Isham Parkyns, of a cottage at Strawberry Hill, gives even more of an impression of a hidden treasure. The perspective is seemingly jarring – why portray the house from a diagonal side profile? One reason may be that it creates a sense of the viewer hiding amongst the trees, peeking out and watching the man go about his business. It is as though we must not make a sound for fear of being spotted; it feels secret and slightly dangerous, as we have come upon another artificial treasure in a pastoral setting.

One could argue that it is the monochromatic nature of a print as oppose to a painting that brings about notions of obscuration, but even when one looks at the 1919 Marshall watercolour of Queen Victoria’s Cottage at Kew, the aesthetics remain the same. Indeed, the trees feature around the outside of the chosen frame, and the view is diagonal to the house. It speaks to the goal, perhaps just as Pope wanted, of recreating the experience of stumbling upon something beautiful and attractive in amongst nature. It is like Lucy discovering Narnia at the back of a wardrobe or Alice falling down the rabbit hole. People have always been enchanted by the prospect of unexpected wonder.

Anyone who has visited or even just seen Strawberry Hill House, knows that Horace Walpole’s property hardly lends itself to his own description of it as a “little play-thing house”. It is large, decadent, bright white, and whimsical. In fact, not only was it a jewel in the landscape itself, but it also housed the eclectic and antiquarian Walpole Collection, just as Pope’s grotto contained treasures from around the world. Throughout this piece, I have discussed grottos and other man-made formations as framed or carved in order to retain a sense of intrigue and richness. Perhaps this is why grottos are common settings for fairy-tales, mythological creatures, and visits to Father Christmas. Places like Strawberry Hill House remind us of fantasy, it could very well stand as an elfin palace, demonstrated especially by the following two prints.

Despite the two prints above being produced over twenty years apart, the composition remains remarkably similar. Owen and Barrow both feed into the fantastical gaze by obscuring the grand property with trees, yet again. The view teases us with what may be behind, and by doing so creates significant distance between viewer and house. The hardened, dark lines of the foreground dominate and the house itself very nearly blends into the sky. All of these artistic choices indicate towards that untouchability, the allure and the fantasy.

These residences are shown to be grottos above ground. The artists want to recreate an experience of stumbling across them in a forest which in turn gives them a magical dimension and therefore a significant level of grandeur. We feel somewhat privileged to have discovered something so beautiful amongst the pastoral foliage, somewhere alluring and inviting. In a sense these properties demonstrate Arcadia, harking back to antiquity and ensuring their high status in Richmond at the time – a town that stood as a bohemia for inspiration, retreat, and extravagance.

[1] Frederick Bracher, ‘Pope’s Grotto: The Maze of Fancy’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 12. 2 (1949), 141-162 (p. 149).

Ella Mackenzie

I am currently studying an MA in Romantic and Victorian Literary Studies at Durham University and started volunteering at Orleans House Gallery during the summer of 2020. A fervent interest in the arts, heritage, and local history led me to want to gain experience at one of Twickenham’s most treasured organisations, and I’m so happy I was able to do so – working alongside the exhibitions in the Study Gallery. I’m excited to see how the eventual lifting of lockdown and Covid-19 restrictions will open up the possibilities for community engagement and education, as well as a more tactile experience in the curated space. My favourite artists would have to be Frederic Edwin Church, John William Waterhouse, Gabriel Loppé and Sandro Botticelli – although many other pre-Raphaelites and Romantics also come close!

You can read all of our volunteers’ articles on works from the collection on our News page.

Would you like to write your own article about the collection? Join our volunteer team and you could be featured next! For this, and other opportunities, visit our Volunteering page.