Wednesday 1 July 2020

In conversation with Mandy Prowse

This week we speak with South West London artist, Mandy Prowse whose sculpture piece for our current Beyond the Frame exhibition was inspired by the fencing shoe of Victorian explorer, Sir Richard Burton whose 200th anniversary we will be celebrating in 2021.

Mandy, could you say a little bit about yourself and what or who got you into art? What were your influences back then?

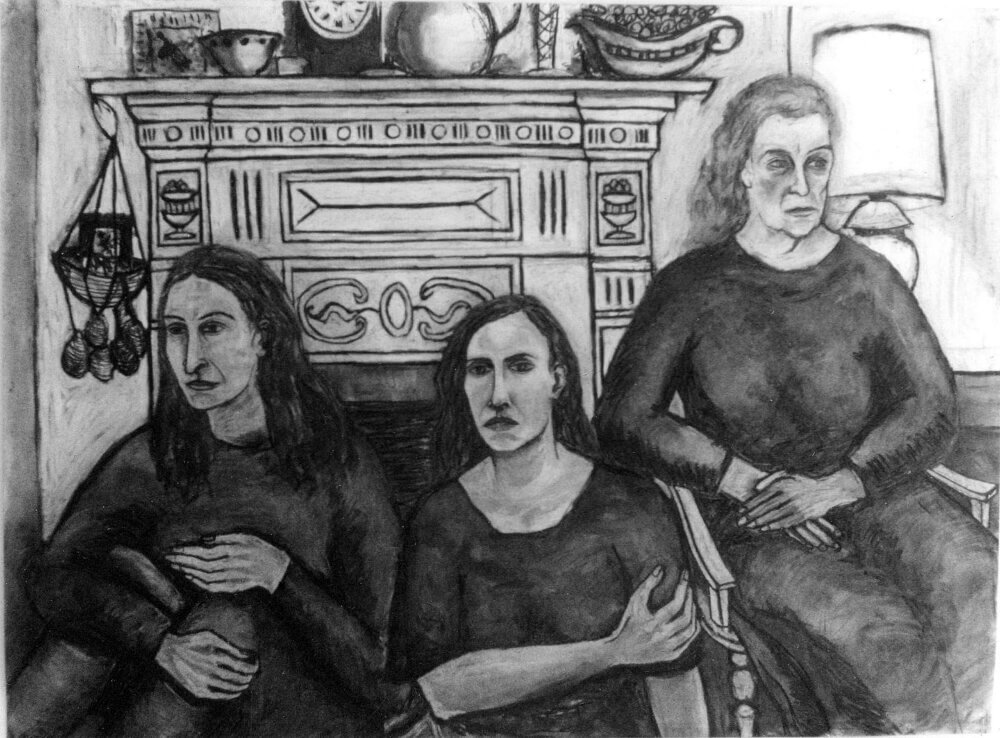

I studied painting and printmaking at Hounslow Borough College and Maidstone College of Art, graduating in 1984. My work was figurative and on a very large scale; I worked in charcoal on paper, oils and watercolour. I grew up in Richmond. When I started making art in the late 1970’s I was inspired both by my mother Annie Lovett-Turner, a sculptor and my maternal grandmother, Natalija Lovett-Turner, a painter. Nata encouraged me to be an artist and inspired me to walk my own path as a young woman with her warmth, generosity, wit and love. I was 28 when Nata died. I gave up painting because I was too heartbroken to continue, and in many ways I never came to terms with losing Nata, who held on to her identity as a Latvian despite being exiled from her country in 1939, firstly to Egypt and then to the UK where she lived and painted until she died in 1990.

I work in a variety of media including drawing, photography, installation and textiles. A self-confessed hoarder of junk and ephemera, I work with the objects that surround me in my home/studio which are collected from car boot sales, charity shops and the street. I am interested in keeping a record of the things I am collecting. I would bring these objects home and they would be absorbed into the everyday accumulation of stuff, hung on the wall or stored in boxes. I started making wall sculptures in 1990, I was inspired by a trip to Egypt where the Hand of Fatima is a recurring image in everyday life. I was on a pilgrimage to trace the footsteps of my Latvian Grandmother Natalija Lovett-Turner, who had lived and worked as an artist in Cairo in the 1940’s. The sculptures were a way of making a precious space to keep lost memories and found objects.

My most recent work has been mainly installation based, using found objects to create stories from the mundane, with everyday domesticated objects. This led to me working on a collection of old cardboard boxes found in flea markets and second-hand shops, their contents are altered and re-configured to create a visual narrative which has the power to startle the viewer when the box is opened. The mundane, the domestic, objets trouvés find new resonances when arranged in unprecedented and provocative configurations with interventions of stitched elements.

You wrote on your Feltbug blogspot about the ‘mostly underground’ group shows that you were involved in after finishing art school. Could you say a little more about those?

I studied an MA in Fine Art (book arts) at UAL Camberwell 2011-2013, at the end of this I was introduced to a group of artists curating their own exhibitions in central London car parks, led by Vanya Balogh, Cedric Christie and Geoffrey Leong, Big Deal. I was invited to take part in 3 shows celebrating Chinese New Year 2017-19, the shows each had a loose theme relating to that year’s Chinese horoscope. This is when I started working on more installation based work, the nature of the space (we were each allocated a car park bay) meant I had to think in a different way about how to make work that would have to be displayed in a dark damp space alongside other artists. It was a revelation that I could come up with an artwork just using the hoard of stuff I had at home, and through placement and associations make a piece of work with a narrative from junk. I have always loved the work of Eva Hess and the Art Povera movement, using found objects and everyday things to make work. There were performances and talks and a general atmosphere of celebration during these shows that felt more meaningful and open than studying in an institution.

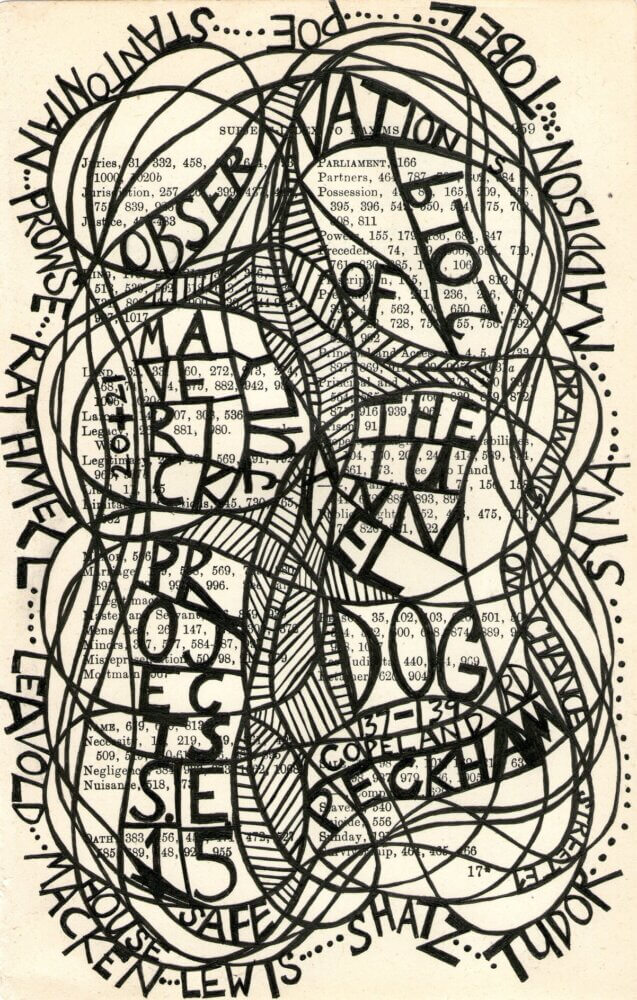

The shapes and lines of your drawings and painting on top of pages from old books, like Observations of a Dog and especially Latin for Lawyers remind me of Joan Miro. Is his work an influence on you?

Yes, I would say that Joan Miro was an early favourite, for his decorative lines and motifs.

When I work on a collection of drawings, I quite often refer to the previous works as I draw to keep a synchronicity in the series and to avoid repetition. In my creative practice I have found that the materials I work with inform the way my work develops. My most recent series of drawings are on book pages from Latin for Lawyers 1937. I do not draw with any preconceived ideas; I allow the drawing to evolve across the page surface in an abstract way. I find myself noticing words or highlighting sentences within the drawing. A relationship develops with the book page as I draw. I begin to engage with the text and it becomes an exercise in reading some rather antiquated and obscure rules relating to the law which then becomes the title of the piece.

I like working on pages that have information on them whether it be words, illustrations or maybe graphs and tables. The quality of the paper varies enormously and there is something magical about working on a piece of paper that is sometimes over 100 years old. Recently the layout of the page has started to take precedence.

My studio is based at home in a domestic environment. Working part-time and being a parent means I feel compelled to work as much as possible in my free time and when I go to see exhibitions I take my tools with me and work on my books as I travel around London. The bus, train or café becomes a temporary studio. I regularly upload my work to the internet via my blog and flickr which I find invaluable for cataloguing my work and for the feedback I receive from other artists. It also acts as a sketchbook for my ideas and inspirations.

What or who is your inspiration today and how is this changing your style or subject matter?

I am currently archiving 40 years of my work, which helps me to make sense of where I am and where I would like to go next creatively. Even though I stopped painting 30 years ago I have continued to make work, in some form, drawing, photography, textiles, design, every day is full of new ideas, I have adapted to making work ‘on the hoof’, my aim for the next few years is to stop and spend some time working on a new series of paintings, the people that inspire me are those that I am closest to, my daughter, my partner, Vic and my family. I will probably go back to my collections of objects and start some still-life studies.

You chose an unusual item from the Borough Collection as the inspiration for your piece, The Burtons enjoyed a daily bout of fencing before breakfast. En-garde! Prêts? Allez! in our Beyond the Frame exhibition, why was that exactly?

Richard Burton’s fencing shoe leapt out at me, it has everything I look for in an object, design, history, textile, shape, form and colour. And it is utilitarian. I have lived in Mortlake for 25 years. With this sculpture I wanted to acknowledge the role of Isabel Burton, his fencing partner (they enjoyed a bout before breakfast!), as a fellow adventurer, writer, companion, lover and cross-dresser, whose lasting legacy was to design a spectacular tomb, when Richard Burton died, a dazzling white, full scale stone replica of their Bedouin tent, which can be found in Mortlake where they are both interred. Richard Burton was known for his theatrical disguises, to enable him to explore other cultures, travelling to countries including India, Arabia and Africa. Isabel Arundell married Richard Burton in 1861. Donning men’s apparel was not uncommon for western women travelling in the near east in the Victorian era and Isabel would join him on expeditions into the desert dressed as a man, pretending that she was Richard’s son. Isabel Burton was the woman behind the man, beyond the frame.

The Burtons enjoyed a daily bout of fencing before breakfast. En-garde! Prêts? Allez!

The Burtons enjoyed a daily bout of fencing before breakfast. En-garde! Prêts? Allez! is a mixed media, vintage French cotton stocking, with hand embroidery and merino wool stuffing, velvet and crepe by Mandy Prowse for the Beyond the Frame exhibition. Find out more about Mandy’s ideas for the piece in her original Artist Statement below.

For the exhibition Beyond the Frame, we were asked to select a work from the London Borough of Richmond arts council collection. I chose the explorer, ethnographer and translator of Arabian Nights, Richard Burton and his fencing shoe. I made a sculpture of a leg, using a vintage French stocking, embroidering an image of Richard and his wife Isabel engaged in a fencing bout.

Richard Burton was known for his theatrical disguises, to enable him to explore other cultures, travelling to countries including India, Arabia and Africa. Isabel Arundell married Richard Burton in 1861. Donning men’s apparel was not uncommon for western women travelling in the near east in the Victorian era and Isabel would join him on expeditions into the desert dressed as a man, pretending that she was Richard’s son.

With this sculpture I wanted to acknowledge the role of Isabel Burton, as a fellow adventurer, writer, companion, lover and cross-dresser, whose lasting legacy was to design a spectacular tomb, when Richard Burton died, a dazzling white, full scale stone replica of their Bedouin tent, which can be found in Mortlake where they are both interred. Isabel Burton was the woman behind the man, beyond the frame.