Tuesday 23 June 2020

Collection Focus – The Art of Attribution

This week we bring you a unique Collection Focus article from volunteer Madeleine.

Learn about how two artists were attributed to our portrait of Queen Caroline, and their artistic styles.

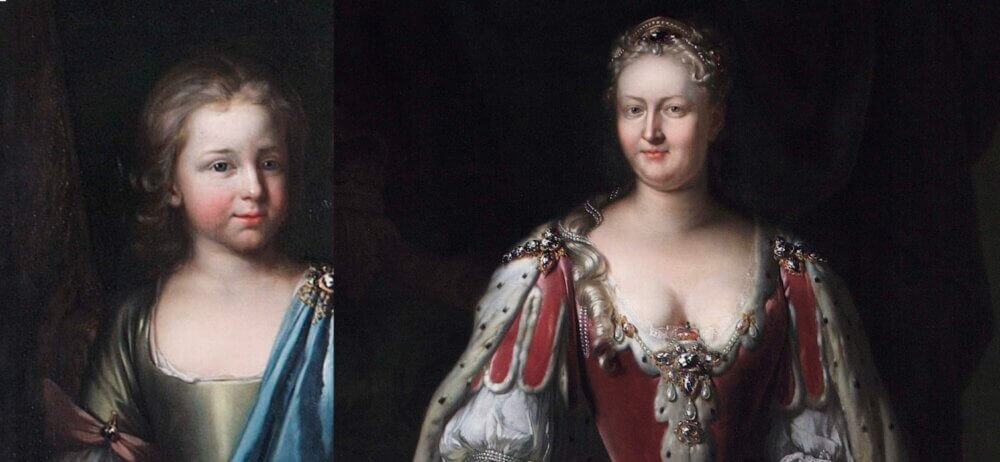

One of our most recognisable works within the gallery is Heroman van der Mijn’s Queen Caroline, c. 1727, which hangs on one of the original outer walls of our Baroque Octagon Room and is the only work of our collection which you are guaranteed to see every time you visit. The double full-length portrait features Queen Caroline and her son William, who would later become the Duke of Cumberland.

The identity of the artist behind the work, however, has been a topic of great discussion throughout the years. As Miranda Stearn, former Arts and Heritage Development Coordinator at Orleans House Gallery, has discussed, for a while the collection catalogue cited Allan Ramsay as its painter, the in-room interpretation attributed Heroman van der Mijn to the work, and more recent publications simply chose to state ‘unknown artist’ due to the uncertainty.

By no means am I qualified to attribute or have experience in attributing works of art, or am I even setting out to reattribute Queen Caroline, but I hope to show you just how easy it is to draw parallels between paintings and artists through a comparison of artistic technique and detailed historical research. Here, I will focus on the two artists who have been attributed to the portrait of Queen Caroline; Heroman van der Mijn and Allan Ramsay. But first, let’s look at the painting itself!

Queen Caroline, Heroman van der Mijn, c. 1727.

Anyone who has visited the gallery and seen this portrait will know exactly what I mean when I say it is impressive in size; the work is a double full-length portrait, and is almost true to the size of the sitters. Queen Caroline stands at the centre of the canvas with her young son at her side. The composition is structured, organised and balanced, as well as hugely spacious. There are no distractions from the subject. The background is lightless, almost pitch-black, which gives the illusion that Queen Caroline and her son are standing in an empty, grand hall. This is greatly significant for two reasons; firstly, it furthers the subject’s importance and secondly, the artist had the opportunity to fill the background but chose not to. This works hand-in-hand to completely elevate the Queen’s importance and authority as the empty background enables the viewer to completely focus on Queen Caroline in all her illuminated glory. It must also be noted that her son, William, is depicted on the same horizontal plane as his mother, suggesting his own significance as son to the Queen.

As touched upon, space within the work is handled with an intense consideration for the subject. The full-length portrait is deeply three-dimensional, despite an almost completely unoccupied background. The subjects themselves are standing naturally in the centre of the canvas, taking up the horizontal planes of the composition. The artist has not deliberately placed any objects or surroundings to mimic a physical frame, enabling the work to be even more open and the viewer is forced into the composition themselves.

The artist’s use of chiaroscuro (an effect contrasted light and shadow) is incredibly important here. The dark background is juxtaposed by the illumination of the subject’s faces and décolletage. The light source is located outside the canvas and acts as a spotlight; Queen Caroline and her son are dramatically thrust into the forefront of the composition, and the viewer is unable to ignore them. The artist has rendered their facial features and gestures with an intricate softness. Their complexions delicately diffuse into their hair and then into the harsh background, ultimately creating an even more dramatic contrast. Additionally, their clothes are subtly highlighted, but nevertheless the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the people themselves first then downwards over their garments.

The material of Queen Caroline and her son’s attire are handled with such incredible skill; overlooking the intricate detail illustrated within the Queen’s skirt, the folds in the drapery of both her and her son’s clothing is breathtaking. The way in which the artist toys with light and shade within the drapery is incredibly naturalistic yet, with such an intense contrast between their complexion and clothes, stark enough to draw attention to the opulence and richness of the subjects. The specific colours used, the deep reds and blues especially, are those which signify wealth and luxury. The choice to use these colours should not be overlooked. Of course, the Queen and William may have been wearing these colours during the sitting process, but this is more about relaying the Queen’s significance and authority to the viewers. In 1727, George II, Caroline’s husband, was crowned King of England, and so Caroline became Queen Caroline – the same year this painting is dated. Ultimately, the intense chiaroscuro rendered by the artist, creates a deeply atmospheric piece without causing the viewer to feel completely intimidated by those they are gazing upon.

Heroman van der Mijn

So we’ve taken a close look at the painting itself, let’s move on to the first of our attributed painters: Heroman van der Mijn. It should be noted that Van der Mijn is the painter which Queen Caroline has most recently been attributed to.

Heroman van der Mijn was an 18th-Century Dutch painter, and it has been said that the artist “founded a dynasty of painters”; 7 of his 8 children were artists! Before settling in England, Van der Mijn worked for the Elector Palatinate until 1716. He resided in Antwerp before moving to Paris in 1718 when Antoine Coypel, the ‘premier peintre du roi’ (First Painter to the King) recommended his work to the Duc d’Orléans. Van der Mijn was then brought to London in 1721 where it has been widely documented that he was particularly well-received by none other than Queen Caroline and her courtiers.

Van der Mijn’s portrait of William IV, the Prince of Orange, inspired the Prince of Wales (Prince George William, son of King George II and Queen Caroline), to ask his sister Anne, Princess Royal, to draw the artist in crayon. He then followed Anne when she married William IV in 1734, becoming Princess of Orange, and moved to the Netherlands where he worked at the Het Loo Palace for two years. After this, Van der Mijn returned to London.

Using our historical knowledge here becomes crucial in the process of attribution. Just by researching the artist’s life and career, pathways open up themselves to us! We have discovered a couple of key points that connect Heroman Van der Mijn to the Queen Caroline portrait within our collection.

Firstly, Heroman Van der Mijn was a known artist to the Duc d’Orléans, Philippe II, during the early 18th-Century. It is plausible that his successors would have also been aware of Van der Mijn’s work; namely, Louis Philippe who came to reside at Orleans House during his exile from France, 1815-17, and again in 1844.

More significantly, in my opinion, is the artist’s direct connection with the sitter. Alongside the artist’s French connections to Orleans House, Heroman Van der Mijn was incredibly favoured by the subject herself, Queen Caroline, who frequently dined at Orleans House in 1729. Here, not only is Van der Mijn linked to Queen Caroline, but Queen Caroline to Orleans House! To further this, Van der Mijn had a close relationship with Queen Caroline’s daughter, the Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, Anne. Of course, even if Heroman Van der Mijn did not paint our Queen Caroline, the way in which a royal painter worked is perfectly detailed by this relationship.

Allan Ramsay (1713-1784) and his ‘Lady Mary Coke’

On the other hand, Allan Ramsay, the alternative painter attributed to Queen Caroline, was a prominent Scottish portrait-painter. Ramsay was born in Edinburgh, 1713, the eldest son of Allan Ramsay, poet and author. From the age of 20, Ramsay studied in London under the Swedish painter Hans Hysing, and at the St. Martin’s Lane Academy. From 1736 to 1739, he worked in Rome and Naples under Francesco Solimena and Francesco Fernandi.

In 1738, Ramsay returned to Britain and, initially, settled in Edinburgh where he attracted considerable attention for his head of Duncan Forbes of Culloden and his full-length portrait of the Duke of Argyll; which was later used on the Royal Bank of Scotland banknotes. Having been employed by the Duke of Bridgewater, Ramsay then relocated to London.

From 1754 to 1757, Ramsay and his second wife, Margaret Lindsay, travelled across Italy visiting Rome, Naples and Tivoli, researching and painting old masters, antiquities and archaeological sites. His Grand Tourists’ portraits laid the foundation for his income during his time in Italy; which included the portrait of James Bateman (son of Sir James Bateman, one of the founding directors of the Bank of England) who was in Rome at the time with his wife.

In 1761, after returning from Italy, Ramsay was appointed Principal Painter in Ordinary to George III. The King commissioned such a multitude of royal portraits to be given to various ambassadors and colonial governments that Allan Ramsay had to employ assistants.

Ultimately, the artist left a series of 50 royal portraits to be completed by his assistant Philip Reinagle before his death in Dover as he was on his way back to Italy in 1784.

In order to effectively discuss the possibility of Ramsay being the artist of Queen Caroline, we need to take a look at Ramsay’s artistic style more closely. It is widely held that Allan Ramsay’s most ‘satisfactory’ productions are some of his earlier pieces, such as the full-length portrait of the Duke of Argyll, his patron. These early works demonstrate an impressive grace and individuality; the pure draughtsmanship in handling flesh-painting and drapery, in particular, is stunning. Within the Richmond Borough Art Collection, we are lucky enough to house one of Ramsay’s works; a print made after a painting of Lady Mary Coke. This full-length portrait of Lady Mary Coke, daughter of John Campbell 2nd Duke of Argyll, is similarly remarkable in the skill and delicacy by which the portrait is managed, specifically the white satin drapery. Let’s dive in!

To begin with, it is worth taking note of the identity of the sitter, as this provides a possible insight to why Ramsay has been attributed to Queen Caroline. Lady Mary Coke (1727-1811) was an English noblewoman who came to be known for her letters and journals which pointed observations of people within her circle, namely political figures. An edition of her letters and journal was published in 1889 dating 1766-1774. She was the youngest daughter of John Campbell (2nd Duke of Argyll) and Jane, who was a maid of honour to Queen Anne and Caroline, at the time Princess of Wales.

Similarly to the portrait of Queen Caroline, Lady Mary Coke stands central within the composition with a spacious background, her drapery gently diffuses into the foreground and her personal significance is demonstrated by both the intricacy of her garments and her size relative to the objects which surround her. Lady Mary Coke stands out against the pillars in the background and holds what seems to be a harp whilst looking directly at the viewer. The overall composition is organised and orderly. Lady Mary Coke’s gestures and posture parallel this; she is composed and commanding the entire centre-foreground, again bearing similarities to Queen Caroline. Ramsay has not placed a visual frame around the work which creates an incredibly open piece and, in my opinion, heightens the importance of the subject. She is able to preside over space within the canvas and outside of it. Saying this, the composition here feels much more crowded. There are numerous objects located both on the same plane as Lady Mary Coke and within the background. If it wasn’t for the spaced out pillars in the background, which create even more depth to the piece, it would become almost claustrophobic. Essentially, these further the illusion of space and depth.

Ramsay handles the space within this work with notable consideration. After all, Lady Mary Coke was a noblewoman and not royalty. This could be why there are specific objects placed within the composition and not so much so within the portrait of Queen Caroline. Lady Mary Coke’s attire, alongside the harp and piano, also help to elevate her significance as the viewer can gage her social standing as an educated noblewoman based on these. On the other hand, Queen Caroline and her son stand naturally at the forefront of the work without many visual prompts other than their clothes whereas Lady Mary Coke is staged much more carefully; she stands at an angle, holding the harp and looking at the viewer.

In terms of the utilisation of light and colour, the way in which Ramsay has employed chiaroscuro is to the exact effect which the artist does so in their rendering of Queen Caroline. The background is well within the shadows and the viewer is only able to make out the exact objects surrounding Lady Mary Coke after some close examination. Lady Mary Coke herself is similarly illuminated by a light source located outside of the composition and, just like within the portrait of Queen Caroline, the light acts as a spotlight; highlighting nothing else but the subject. Unfortunately, our print is monochrome making an assessment of colour and tone much harder. Despite this, and as I touched upon briefly, there is great discussion of Ramsay’s detail in depicting drapery and human flesh which is entirely visible to us within Lady Mary Coke. The folds in her dress have been illustrated so delicately and with such attention to light and shade which enables the sitter to dazzle in the light, despite the monochrome palette. She is completely illuminated and stands out so strikingly against the dark background. The severity of chiaroscuro and the spotlight nature of the light here is interestingly similar to that employed within Queen Caroline.

Final Thoughts

As we have unpicked, there are considerable similarities between the two artistic styles of both Heroman Van der Mijn and Allan Ramsay. With the help of Ramsay’s print, Lady Mary Coke, we have been able to draw these similarities (and differences) out further. The composition and manipulation of light are two of the most striking parallels between the two artists.

I personally believe that Heroman Van der Mijn is the artist behind Queen Caroline as there are connections between the artist and sitter, and even her family and Orleans House, that absolutely cannot be ignored. Equally, his other works prove to be composed in a similar manner with similar palettes and technique. It simply feels easier to attribute the portrait of Queen Caroline to Heroman Van der Mijn. Most significantly, the artist was personally favoured by both Queen Caroline and her family, as well as her courtiers. Van der Mijn had also been recognised by royal households throughout his career. To me, to attribute the work to Allan Ramsay brings up more questions than answers despite the noble circles Ramsay worked within.

All in all, it is very easy to see and to understand how art historians have stumbled over the question of ‘who painted Queen Caroline’ throughout the years. Both Van der Mijn and Ramsay share a similar style, focused on portraiture, and employed chiaroscuro to an amazing, dazzling effect. Not only does the question in focus demonstrate just how ‘artful’ attributing artists to works really is, but it also highlights the very real possibility of misattributing works of art – even when you have access to participate in extensive research!

If you would like to know more about the mission to attribute Queen Caroline to its artist at Orleans House Gallery, click here!

Madeleine Luxton

I have recently graduated from the University of East Anglia with a degree in History and History of Art. I am thoroughly enjoying my time exploring the art world and have already become enamoured with one of London’s hidden gems – Orleans House Gallery! Volunteering at Orleans House Gallery has allowed me to meet fellow art enthusiasts and to broaden my passion in helping the art world become much more accessible. My favourite artists are Edouard Manet, Diego Rivera, Robert Rauschenberg and Tracey Emin.

As Madeleine mentions, you can view the portrait of Queen Caroline on display in the gallery, on the one of the outer walls of the Octagon Room.

Do you want to learn more about Queen Caroline’s history with Orleans House? Join us on one of Heritage Tours to discover about her visit, plus the 300 years of the house at the forefront of importance in the local community. More information on the tours is available here.

Are you interested in looking at an artwork critically? Read Madeleine’s guide to visual analysis here.

Join our volunteer team and you can write about the collection! For this, and other opportunities, visit our Volunteering page.