Thursday 21 May 2020

Burton: Exploring without Boundaries

In view of next year’s bicentenary of the birth of Victorian explorer Sir Richard Burton, Emily Lunn, Heritage Project Manager for the Environment Trust, talks to Chris Burton, our Exhibitions and Collections Arts Officer, about the many personal belongings of the great man in the Borough Art Collection. The interview first appeared on 18 May 2020.

What makes up the Burton collection?

The Burton Collection is made up of an eclectic mix of personal effects and belongings once owned by Victorian explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890).

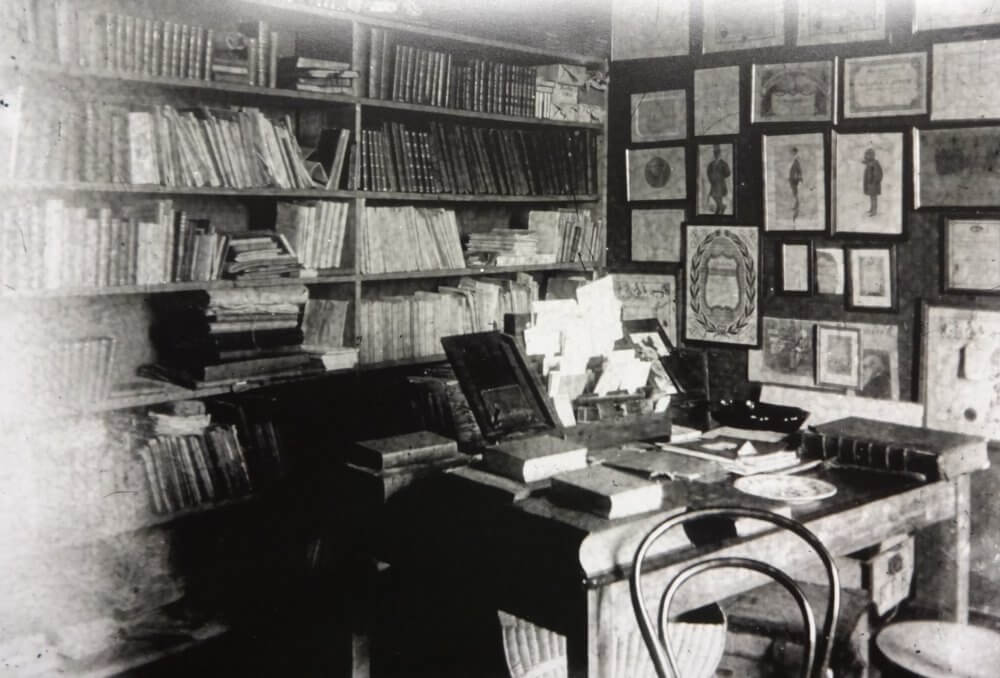

A substantial portion of the collection includes paintings by Albert Letchford, a British painter and close friend of the Burtons in their later years. Most of Letchford’s paintings accurately depict several interiors of the Burtons’ home and surrounding scenery in Trieste, Italy. In addition, a couple of portraits by Letchford are held in the collection too, including a large 7ft tall oil painting of Burton in fencing gear.

Some of the more peculiar items in the collection reflect the unusual life Burton lived, the cultures he indulged in, the people he encountered and the interactions he had. A prime example would be the bone necklace he received as a gift from the King of Dahome (now Benin) during his stay there. The tribe were believed to be cannibals and the necklace said to be made from human bone!

The collection also contains items Burton took with him on his renowned pilgrimage to Mecca. Examples include a secret stainless-steel document cylinder with hidden compartments for storing sketches and notes he made in situ and a textiles “housewife” kit for repairing garments on the move.

There is a wide collection of weaponry, believed to be largely acquired in the UK. These include a handful of British and Scottish infantry swords, a mixture of South African spears and a pistol, said to have been part-designed by Burton to be easier to handle and fire from horseback.

How did the collection end up at Orleans House?

It is thanks to Isabel Burton (1831-1896), who lovingly curated the items left to the nation that the Burton Collection exists.

On the death of the explorer, writer and translator Sir Richard in 1890, funds were so limited that Lady Isabel Burton was forced to request donations in order that she could give her husband the resting place he always wanted – above ground in an Arab tent which is under the care of Environment Trust.

In return, Isabel pledged a number of items to the nation. These paintings, photographs, books and personal effects were transferred from Camberwell Public Library in 1969 and shared between Orleans House Gallery and Richmond Local Studies Collection. The Burton Collection is on loan from Southwark Council.

You have a mysterious talisman in the collection that was once owned by Burton. Can you tell me more about it and how you went about researching it?

That’s correct! A small stone which until recently had been incorrectly catalogued as a “meteorite from Mesopotamia” has now been identified as an Islamic talisman, found by Burton while exploring the Midian in north west Arabia.

The expedition was funded in 1877 by the Khedive of Egypt, Ismail I, at a time of financial uncertainty to excavate large amounts of gold and silver Burton suspected to exist there. Although the exercise failed to uncover much in the way of precious metals, the trip did however prove to be a success with regards to finding items of archaeological and mineralogical interest.

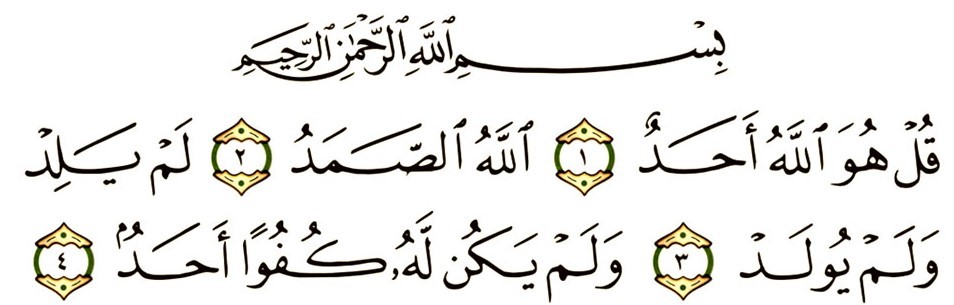

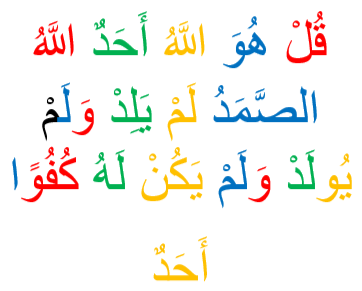

The talisman itself, both ovoid and conical in shape includes a suspension hole so that it can be worn as a pendant and possesses an ancient Arabic inscription reading the 112th Quranic chapter, al-Ikhlas also known as al-Tawḥīd. The chapter is deemed by some as one of the most significant chapters in the Quran, a short, yet key declaration of the unity to one god and a popular choice in daily prayer among many Muslims today.

Burton states, in his personal account (Land of the Midian Revisited):

“and yet our old acquaintance, Mohammed el-Musalmáni”… “he aided us in collecting curiosities, especially a chalcedony (agate) intended for a talisman and roughly inscribed in Kufic characters, archaic and pointed like Bengali, with the Koranic chapter (xcii.) that testifies the Unity, ‘Kul, Huw’ Allah’ “

Translated to English, the stone reads:

Say: He is God, (who is) One.

Qul, Huwa Allah, Ahad

God the absolute/eternal

Allah a-Samad

He neither begets nor was He begotten

Lam yalid walam yulad

And there is no one equal to Him.

Walam yakun lahu kufuwan ahad

How did you decipher the inscription?

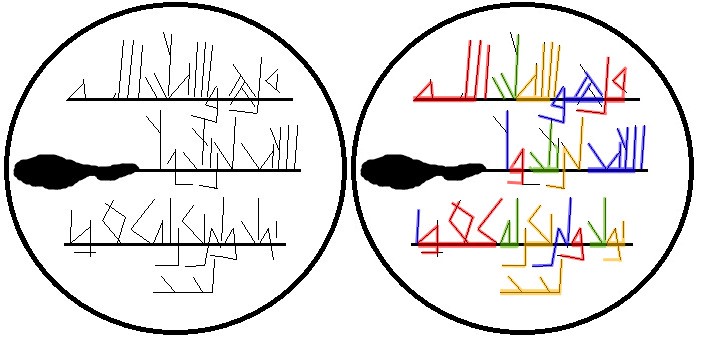

The process of deciphering the inscription was extremely challenging. A lot of research was spent looking at as many archaic inscriptions online image-searches could uncover. And this led to very little in the way of promising results. Various Arabic speakers, translators and specialists in ancient languages were contacted, but were unable to give any absolute answers, instead highlighting its similarities to other ancient languages, like Celtic Ogham, Scandinavian Runes and Greek.

I later found that both the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum had similar objects in their collection too, with strikingly similar engravings and all of which identified as being an early form of Arabic. Which corresponded with my initial thoughts, particularly when looking at the last word “ahad”, centred on the fourth and final row. Those specimens were also useful in identifying some of the more ambiguous markings. The first “floating triangle” on the top line for instance (Qāf ق), when compared to similar inscriptions, becomes clear that it is missing an adjoining stroke.

My research continued day and night, using online Arabic alphabet character-typers and translation services to try and recreate the top line as closely as possible. I assembled as many comparable variations of Arabic as possible and translated the best matches to see if any made sense. I then took the strings of text which translated well and searched online to see if any were common in Arabic literature. This was a tiring process, as there are 4 variations of most Arabic letters and in some cases, can merge together to form a new shape altogether! It felt like an uphill battle and didn’t seem to bring much in the way of promising results. In between attempts I would research other areas relevant to both Islamic and pre-Islamic Middle-Eastern culture as well as scanning through the archive of Burton publications at Orleans House Gallery.

Eventually, after more recycling and replacing of search terms in Google, I stumbled upon Burton’s quote (from The Land of the Midian Revisited) and was able to find a recent version of “Koranic chapter (xcii.) that testifies the Unity”.

Although I couldn’t find a version with the same numerical identity as what Burton had communicated (“xcii” meaning 92), it was clear to me that I was looking at the correct passage, as the English pronunciation “Qul, Huwa Allah” when spoken, is phonetically the same as Burton’s “Kul, Huw’ Allah“. Moments after making this discovery, when casting my eyes over the Arabic scripture I found that the top line, perfectly matched one of my prior attempts, further supporting the idea!

Despite having the correct chapter at hand to work from, a lot of imagination and patience was required to work out the more cryptic sections. To the point that I would often question the parts which correlated. There are two instances of the word “ahad” (‘one’) for instance, as mentioned previously there’s one on the last row, represented in the way many would find easy to identify, and the other, a condensed form of the word on the top row. This asymmetry along with many other inconsistencies made sure there were hurdles every step of the way!

Dating the item opens another mystery. It’s worth mentioning that when searching online for examples of engraved rocks from the Middle-East, it was clear to me that the gemstone-pendants which are most similar in material, size and shape could not be more different with regards to the kinds of engravings they generally possess. These items, the closest of which known as pre-Islamic Persian stamp-seals are conversely engraved with depictions of people, wildlife and nature and only rarely complemented with the owner’s initials in a form of Persian. As these possessions were used by the owner to sign official documents, the engravings are etched in reverse so that the printed relief of the image faces the correct way around. Burton’s talisman on the other hand, does not!

The other side to this, is that nearly every Arabic-inscribed gemstone found during my investigation, which were produced from the same kinds of minerals as the Persian stamp-seals made prior, are completely different in shape. To put it simply, they tend to be less pebble-like, flatter and angular in the way they have been designed. With this in mind, I would be urged to presume that the rock was initially fashioned in Persian culture and later re-engraved during the Islamic period. I would also add, that based on account of its shape, in my opinion falling somewhere between stamp seals typically associated with neo-Assyrian and Sassanid Persia and also taking into account the purity of the mineral itself, would lead me to believe that it may have been first shaped in the Achaemenid period, nearly 2500 years ago!

The collection is extensive – not everything is on display. What do you have in archive?

That’s right. Although most of the prominent items in the Burton Collection are now thankfully out on permanent display, some still remain in storage. These include most of Albert Letchford’s paintings, including the large portrait of Burton in fencing gear; Burton’s Murshid’s Diploma in the Kadiri Order of Sufism, which has recently been translated; the Islamic talisman and many black and white photographs of the Burtons in Trieste. We also have a small yet charming framed manuscript by Burton in gold ink on blue paper, which hung above Burton’s bed reading “This also will pass” in Persian.

Our long-term aim is to include a few of these more smaller items to the Study Gallery display, Burton’s Persian manuscript, his recently translated talisman and freshly translated Arabic diploma being the main contenders. The enormous 7ft portrait of Burton in fencing gear by Albert Letchford, which is too tall for the Study Gallery, will hopefully go out on display again next year, for the first time in over two decades as part of a main gallery exhibition celebrating 200 years since the birth of the legendary polymath.

And finally, what is your favourite item in the Burton Collection?

This is of course a difficult question, in that, I have recently developed an obsession for the talisman and ancient inscribed microcrystalline variants of quartz in general! So, I can’t deny the fact that, at the moment, the talisman is still my favourite.

But I really want to give a different answer, something which has resonated with me in all times, like the photos of Burton looking at the camera from a diagonal angle, with an eyebrow raised, a big Persian-style moustache, resembling a man not too dissimilar from a young Freddy Mercury… another hero of mine!

Find out more about the Environment Trust’s project Burton: Exploring Without Boundaries and their work to restore the mausoleum.

You can also find more about Sir Richard Burton’s items in the collection here.